2000 Election

Results, The Campaigns

The

2000 presidential election pitted Republican George W. Bush, governor

of Texas and son of former US president George H.W. Bush, against

Democrat Al Gore, former senator from Tennessee and vice president in

the administration of Bill

Clinton. Because

Clinton had been such a popular president, Gore had no difficulty

securing the Democratic nomination, though he sought to distance

himself from the Monica Lewinsky scandal and Clinton’s impeachment

trial.

Bush

won the Republican nomination after a heated battle against Arizona

Senator John McCain in the primaries. He chose former Secretary of

Defense Dick Cheney as his running mate.

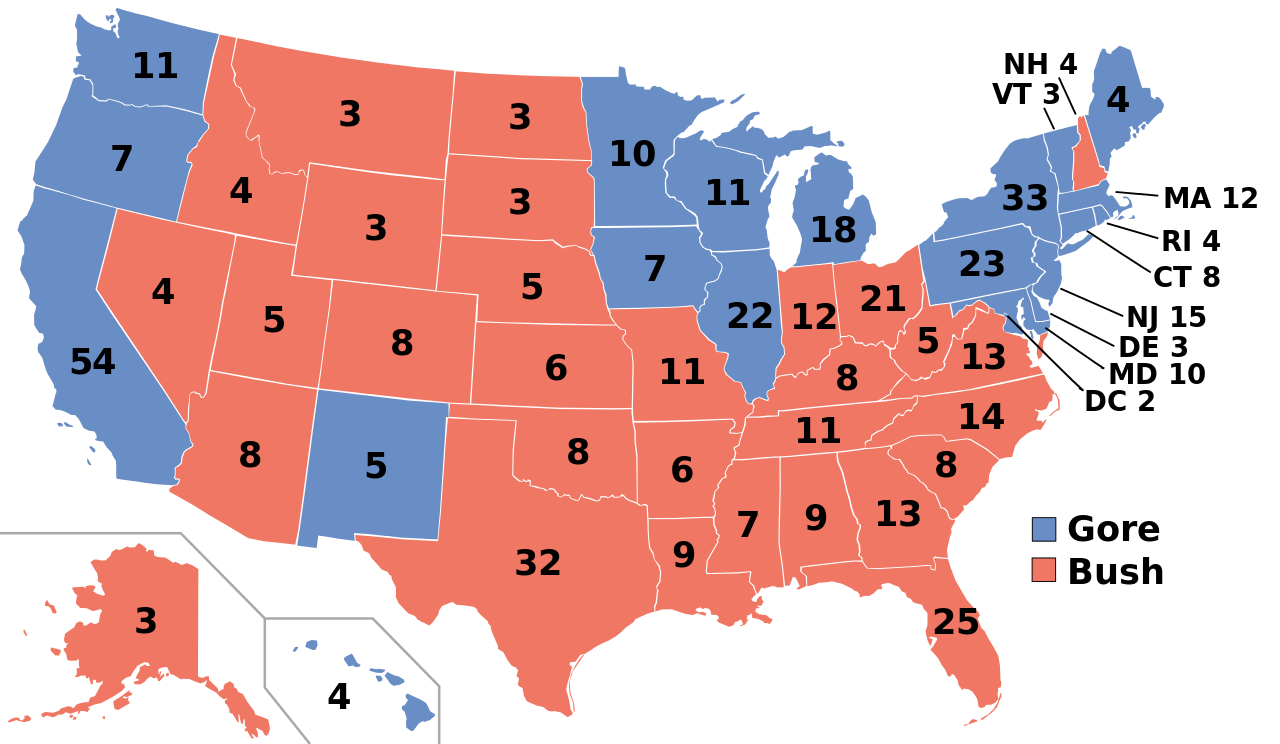

On

election day, Gore won the popular vote by over half a million votes.

Bush carried most states in the South, the rural Midwest, and the

Rocky Mountain region, while Gore won most states in the Northeast,

the upper Midwest, and the Pacific Coast. Gore garnered 255 electoral

votes to Bush’s 246, but neither candidate won the 270 electoral

votes necessary for victory. Election results in some states,

including New Mexico and Oregon, were too close to call, but it was

Florida, with its 25 electoral votes, on which the outcome of the

election hinged.

The

Campaigns

In

their presidential campaigns, both candidates focused primarily on

domestic issues, such as economic growth, the federal budget surplus,

health care, tax relief, and reform of social insurance and welfare

programs, particularly Social Security and Medicare (Election 1).

The

election of 2000 merged or obliterated many of [the previous

divisions between the two parties]. During the Clinton years,

Democrats overcame their losing reputation on moralistic issues, as

Clinton became identified with such stands as harsh treatment of

criminals (including support for the death penalty) and welfare

reform. The president maintained his popularity even after revelation

of his sexual immorality, as seen in the failure of the Republican

effort to impeach and remove him from office.

In

2000 Republicans also moved away from previous unattractive

positions. On the economic dimension, no longer opposed to all

government programs, the party under Governor Bush proposed new

policies to improve education, expand health care, and add funds and

programs to Social Security and Medicare. Still conservative, the

Bush Republicans now modified their ideology by proclaiming a new

"compassionate" outlook and reduced their emphasis on moral

issues, particularly abortion. Without overt change in his pro-life

stance, George W. Bush gave only fleeting attention to the previously

divisive issue, promising no more than a ban on unpopular and rare

late-term ("partial birth") abortions.

Differences

remained significant, but the election campaign was notable for the

similarity of the issues stressed by the candidates and for the

disappearance of older conflicts. A generation earlier, in 1972,

Republicans had accused Democrats of favoring "acid, amnesty,

and abortion"; that bitter campaign would be later remembered

for Richard Nixon's efforts to destroy his opponents and subvert the

Constitution in the Watergate break-in.

The

old controversies were gone or had become consensual policies. Drug

usage was condemned, and abortion was ignored. Vietnam, the conflict

that had defined a generation and its lifestyle, was now a country to

be visited by Clinton, once a draft resister and now the U.S.

commander-in-chief. Emblematic of the change was that the Democratic

party, once the arena for the greatest antiwar protests, nominated

Gore, a volunteer who had actually served briefly in the war zone,

while the Republicans nominated Bush, who had found a safe billet in

the Texas Air National Guard.

There

remained a basic philosophic difference between the parties and their

leaders. Republicans' instincts still led them first to seek

solutions through private actions or through the marketplace, while

Democrats consistently looked for government solutions. That

difference was evident in such fundamental questions as allocation of

the windfall surpluses in the federal budget: Bush sought a huge

across-the-board cut in taxes, while Gore proposed a panoply of new

government programs and tax cuts targeted for specific policy

purposes.

Similar

differences could be seen on other issues emphasized during the

campaign. To improve education, Bush relied on state programs and

testing, while hinting at his support for government vouchers that

parents might use for private-school tuition; Gore proposed new

federal programs to recruit teachers and rebuild schools. To provide

funds for Social Security, Bush proposed that individuals invest part

of their tax payments in private investment accounts, while Gore

would transfer other governmental funds into the Social Security

trust fund. This philosophical difference could be seen even in the

most intimate matters, such as teenage pregnancy, where Republicans

relied on individual morality, namely, sexual abstinence by

adolescents, while Democrats supported sex education programs, which

might include distribution of condoms in public schools.

…

Bush

had made some efforts to gain more minority votes, giving blacks

prominent roles in the party convention and arguing that some of his

programs, such as educational testing, would particularly benefit

this group. These appeals turned out to be fruitless, however, given

the Republican's conservative position on welfare issues and

affirmative action. Black groups, such as the N.A.A.C.P., mounted a

multimillion-dollar campaign to increase minority turnout, expecting

that the mobilized voters would be Democrats. Although the black

proportion of the electorate remained essentially unchanged at 10

percent, these efforts probably were decisive in close northern

states. It would require more than televised black faces to win black

votes for the Republicans.

…

Other

ethnic minorities also supported the Democrats. Both parties paid

special attention to Latinos, knowing that they would soon be the

largest nonwhite group in the population and that they already

comprised a significant voting bloc in critical states such as

California, Texas, and Florida.

…

Gore's

policy agenda was a more "female" agenda, in a political

rather than biological sense: the vice president focused on questions

likely to be of more concern to women because of their social

situation. The social reality in the United States is that women bear

a greater responsibility for children's education and for health care

of their families and parents, and that women constitute a

disproportionate number of the aged. This reality was reflected in

political concerns, as women saw education, health care, and Medicare

as the principal issues of the election. For these reasons, Gore's

greater readiness to use government to solve these problems might

appeal particularly to women.

A

gender gap has two sides, however, and in 2000 it reflected men's

preferences even more than women's. Bush's appeal, too, can be found

in particular issues. The social reality is that men are more likely

to be the principal source of family income and to assume greater

responsibility for family finances. This reality was again mirrored

in issue emphases, with men making the state of the economy and taxes

their leading priorities, with defense and Social Security of lesser

importance.

The

gender difference in issue focus was the foundation of gender

difference in the vote. Gore was favored among voters who emphasized

the "female" issues of health care (an advantage of 31

percent), education (8 percent), and Social Security (18 percent),

and Medicare (21 percent). But Bush was favored far more strongly on

taxes (a huge advantage of 63 percent) and on world affairs and

defense (14 percent), as well as on lesser issues that brought male

attention, such as the stereotypically gendered issue of gun

ownership.

The

presidential race should have been a runaway, according to

precampaign estimates. In the end, to be sure, the outcome came down

to miscounting or manipulation of the last few ballots. Analytically,

however, the puzzling question is why Gore did so badly, not why Bush

won.

The

economy, usually the largest influence on voters, had evidenced the

longest period of prosperity in American history, over a period

virtually identical with the Democratic administration. A second

predictor, the popularity of the incumbent president, also pointed to

a Gore victory, for President Clinton was holding to 60-percent

approval of his job performance. In elaborate analyses just as the

campaign formally began on Labor Day, academic experts unanimously

predicted a Gore victory. Their only disagreements came on the size

of his expected victory, with predictions of Gore's majority ranging

from 51 to 60 percent of the two-party popular vote.

The

academic models failed. It is simpler to explain Clinton's inability

to transfer his popularity to his selected successor. Vice presidents

always labor under a burden of appearing less capable than the

sitting chief executive, and there is a normal inclination on the

part of the electorate to seek a change. Previous incumbent vice

presidents, such as the original George Bush in 1988 and Richard

Nixon in 1960, had borne this burden in their own White House

campaigns, but Gore's burden was even heavier, because he needed to

avoid contact with the ethical stain of Clinton's affair with a White

House intern, Monica Lewinsky.

There

are at least three possible explanations. First, because prosperity

had gone on so long, voters may have come to see it as "natural"

and unrelated to the decisions and policies of elected politicians.

Second, voters might not know whom to praise and reward for their

economic fortunes, since both parties in their platforms claimed

credit for the boom. These explanations seem weak, however, because

two out of three voters believed Clinton was either "somewhat"

or "very" responsible for the nation's rosy conditions.

A

third explanation, better supported by the opinion data, finds that

Gore did not properly exploit the advantages offered by his

administration's economic record. In his campaign appeals, Gore would

briefly mention the record of prosperity but then emphasize his plans

for the future. The approach was typified by his convention

acceptance speech:

[O]ur

progress on the economy is a good chapter in our history. But now we

turn the page and write a new chapter.... This election is not an

award for past performance. I'm not asking you to vote for me on the

basis of the economy we have. Tonight, I ask for your support on the

basis of the better, fairer, more prosperous America we can build

together.

Rhetorically

and politically, Gore conceded the issue of prosperity to Bush. …

…

Gender

may also have played a role in undermining Gore's inherited advantage

on the economy. Although voters who emphasized this vital factor did

favor the vice president (59 to 37 percent), he gained far fewer

votes (a 15-percent gain) on the issue than Clinton had four years

earlier (34 percent), even though the economy had strengthened during

the period. Here, too, as on issues generally, Gore emphasized the

"female" side of his policy positions, such as targeting

tax cuts toward education or home care of the elderly. He offered

little for men who would not benefit from affirmative action in the

workplace or who would use money returned from taxes for other

purposes. As a result, he gained far less from men (57 percent) than

from women (68 percent) who gave priority to economic issues.

In

theoretical terms, the vice president turned the election away from

an advantageous retrospective evaluation of the past eight years to

an uncertain prospective choice based on future expectations.

Because the future is always clouded, voters often use past

performance to evaluate the prospective programs offered by

candidates, but Gore did little to focus voters' attention on the

Democratic achievements. As the academic literature might have warned

him, even in good times "there is still an opponent who may

succeed in stimulating even more favorable future expectations. And

he may win."

More

generally, Gore neglected to put the election into a broader context

– of the administration's record, of party, or of the Republican

record in Congress. All of these elements might have been used to

bolster his chances, but he, along with Bush, instead made the

election a contest between two individuals and their personal

programs. In editing his own message so severely, Gore made it less

persuasive. If the campaign were to be only a choice of future

programs, with their great uncertainties, a Bush program might be as

convincing to the voters as a Gore program. If the election were to

be only a choice of the manager of a consensual agenda, Bush's

individual qualities might well be more attractive.

The

Democratic candidate had the advantage of leadership of the party

that held a thin plurality of voters' loyalties. His party was

historically identified with the popular programs that were

predominant in voters' minds – Social Security, Medicare,

education, and health care – and the Democrats were still regarded

in 2000 as more capable to deal with problems in those areas. Yet

Gore eschewed a partisan appeal. In the three television debates,

illustratively, he mentioned his party only four times, twice citing

his disagreement with other Democrats on the Gulf War, and twice

incidentally. Only Bush would ever commend the Democratic party,

claiming a personal ability to deal effectively with his nominal

opposition.

Gore

neither challenged this argument, nor attacked the Republicans who

had controlled Congress for the past six years, although promising

targets were available. The vice president might have blamed

Republicans for inaction on his priority programs, such as Social

Security and the environment. He might have drawn more attention to

differences on issues on which his position was supported by public

opinion, such as abortion rights or gun control. He could even have

revived the impeachment controversy, blaming Republicans for dragging

out a controversy that Americans had found wearying. The public had

certainly disapproved of Clinton's personal conduct, but it had also

steadily approved of the president's job performance. That

distinction could have been the basis for renewed criticism of the

Republicans. Yet Gore stayed silent.

Gore's

strategy was based on an appeal to the political center and to the

undecided voters gathered there. At the party convention and in his

acceptance speech, he did try to rouse Democrats by pointing to party

differences – and the effort brought him a fleeting lead in opinion

polls. From that point on, however, moving in a different direction,

he usually attempted to mute those differences, and his lead

disappeared. If there were no important differences, then Democratic

voters had little reason to support a candidate whose personal traits

were less than magnetic. Successful campaigns "temporarily

change the basis of political involvement from citizenship to

partisanship." By underplaying his party, Gore lost a vital

margin of votes, as more Democrats than Republicans defected.

…

When

it came to individual character traits, however, Bush was deemed

superior on most traits, particularly honesty and strength of

leadership. He was also viewed as less likely "to say anything

to get elected" and less prone to engage in unfair attacks. …

(Pomper 201).

Works

cited:

“The

Election of 2000.” The

Khan Academy. Web.

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/modern-us/1990s-america/a/the-election-of-2000

Pomper,

Gerald M., “The

2000 Presidential Election: Why Gore Lost.” Political

Science Quarterly,

Summer 2001, volume 116, issue 2. Web.

https://www.uvm.edu/~dguber/POLS125/articles/pomper.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment